There’s this glurgy poem about the Earth being a few feet in diameter. It’s an incredibly cheesy poem (and will you check out the cheesy website I found when I went searching for it to write this post), but I’m kind of partial to it for what it reveals about human psychology. It ends as follows:

This gap, between real things and representations of things, is at the heart of something I’ve been struggling to get my head around in recent months. The passion I see for stories, be they movies, games, or—gasp—sometimes novels, is something that I share, and yet it boggles me that as much as they affect culture in a broad sense, they seem to often have little impact on the individuals most devoted to them.

I f the Standing Rock land defenders were nine feet tall, blue, and had pointed ears and cat eyes, would the viewers who made a shitty film $2.788 billion give some of that time and money in the fight against DAPL? If the cops gunning down unarmed black people in the streets were wearing Stormtrooper armour instead of blue uniforms, would white geeks sympathize with Black Lives Matter’s rage? If North Americans of different classes were divided into twelve large geographical districts rather than a patchwork of segregated neighbourhoods ripe for gerrymandering, would struggle against the 1% become a more palatable idea outside of the typical activist demographic?

f the Standing Rock land defenders were nine feet tall, blue, and had pointed ears and cat eyes, would the viewers who made a shitty film $2.788 billion give some of that time and money in the fight against DAPL? If the cops gunning down unarmed black people in the streets were wearing Stormtrooper armour instead of blue uniforms, would white geeks sympathize with Black Lives Matter’s rage? If North Americans of different classes were divided into twelve large geographical districts rather than a patchwork of segregated neighbourhoods ripe for gerrymandering, would struggle against the 1% become a more palatable idea outside of the typical activist demographic?

Speaking as a responsible adult, we often worry about the messages young people take from media. Can a kid playing a violent video game distinguish between fantasy and reality (my own response to this is nuanced; in most cases yes, in some cases, actually not so much, or the military wouldn’t use video games for recruitment)? But I think in focusing on that, we often neglect to examine why these stories exist in the first place, and what we stand to learn from them.

Genre stories in particular are often morality tales; the more elevated a story is in pop culture, the more likely it is to be this. They train us to root for good versus evil, the underdog versus the oppressor, and showcase heroes for whom force is a last resort, but for whom force ultimately becomes a necessity in the face of injustice. Viewed superficially, these narratives can be dangerous; one only needs to look at the far right to see how easily the straight white cismale can be reframed as the underdog, fighting against a vast liberal machine seeking to take away his freedom of expression, while subsequently dehumanizing the Other as some sort of Tolkien-esque orc mob. They remove nuance (not that nuanced genre fiction doesn’t exist; it absolutely does, but it’s rarely elevated to the point of cultural touchstone). The “bad” side seldom has a motivation beyond money, revenge, or power, even while individual villains may be complex and interesting characters.

Genre stories in particular are often morality tales; the more elevated a story is in pop culture, the more likely it is to be this. They train us to root for good versus evil, the underdog versus the oppressor, and showcase heroes for whom force is a last resort, but for whom force ultimately becomes a necessity in the face of injustice. Viewed superficially, these narratives can be dangerous; one only needs to look at the far right to see how easily the straight white cismale can be reframed as the underdog, fighting against a vast liberal machine seeking to take away his freedom of expression, while subsequently dehumanizing the Other as some sort of Tolkien-esque orc mob. They remove nuance (not that nuanced genre fiction doesn’t exist; it absolutely does, but it’s rarely elevated to the point of cultural touchstone). The “bad” side seldom has a motivation beyond money, revenge, or power, even while individual villains may be complex and interesting characters.

This is the obvious reason for distinguishing fiction from reality, but I think most adults are able to do that. What is more confusing for me is that the social usefulness of such morality tales often gets lost in the shuffle.

I hate to be harping on the antifa thing with so many posts, but it’s a good example of where I feel lessons of fiction have utterly failed the casual citizen. The typical anti-antifa (dear fuck, what an awkward construction) post I see on Facebook focuses on two things: violence and masks. Because antifa are sometimes violent—even though in reality only a small number of antifa commit actual violence in a small percentage of anti-fascist work—and we dislike Nazis because Nazis are violent, the two are morally comparable. This is an easily debunked argument, though I imagine its proponents must have a difficult time wrapping their heads around, say, World War II.

I hate to be harping on the antifa thing with so many posts, but it’s a good example of where I feel lessons of fiction have utterly failed the casual citizen. The typical anti-antifa (dear fuck, what an awkward construction) post I see on Facebook focuses on two things: violence and masks. Because antifa are sometimes violent—even though in reality only a small number of antifa commit actual violence in a small percentage of anti-fascist work—and we dislike Nazis because Nazis are violent, the two are morally comparable. This is an easily debunked argument, though I imagine its proponents must have a difficult time wrapping their heads around, say, World War II.

The mask issue is what I find more interesting. One meme I saw equated antifa to KKK, because both wear masks, and if you believe in your convictions, you wouldn’t hide your face. This was from a nerd, though journalists also ask this question frequently. Presumably, nerds and journalists are both familiar with the tropes of superhero comics, in which both heroes and villains often wear masks to disguise their identities.

“But wait, Sabs. You’re not living in a comic book! This is real life.”

Okay. But. Fiction exists for a reason, which is to tell us stories about who we are and why people do the things they do. Otherwise, there is no point to it; the stories we tell would have no resonance if they were meaningless.

So why does Batman wear a mask? Partially to invoke fear, but also to, oh, protect his friends from retaliation. To, to frame it in real-life terms, avoid getting doxxed. We can—and I do—argue that perhaps donating his copious billions to build up Gotham’s infrastructure and mental health services might go a lot farther in terms fixing the root problems plaguing the city, but I don’t think even the most hyper-critical pedant would argue that Batman’s failures are because he wears a mask. Or because he is secretly ashamed of his beliefs. Or even that he is morally equivalent to the villains he fights, either because of aesthetics (mask) or actions (violence), despite the existence of grimdark comics revisionism.

So why does Batman wear a mask? Partially to invoke fear, but also to, oh, protect his friends from retaliation. To, to frame it in real-life terms, avoid getting doxxed. We can—and I do—argue that perhaps donating his copious billions to build up Gotham’s infrastructure and mental health services might go a lot farther in terms fixing the root problems plaguing the city, but I don’t think even the most hyper-critical pedant would argue that Batman’s failures are because he wears a mask. Or because he is secretly ashamed of his beliefs. Or even that he is morally equivalent to the villains he fights, either because of aesthetics (mask) or actions (violence), despite the existence of grimdark comics revisionism.

Of course, I am not just talking about violence—in fact, critiques of left-wing activism often, at their root, have little to do with what any reasonable person would deem violence. Any political action outside of state-sanctioned action—which is to say, voting, and possibly calling your representative if we’re feeling generous—meets with the most vicious criticism from people looking for an excuse to either disparage the cause or not do anything themselves. There is nothing remotely violent about, say, blocking a major street with a peaceful demonstration, but large swathes of the right and centre are quite comfortable with running over protestors who do so. They would prefer it, I suspect, if we did not push back at all.

This, despite the presence of myths that tell us to venerate individuals and groups that worked outside of the system, whether fictional or real. The Civil Rights movement may very well be a fairy tale for all that an average commentator knows about it; those who idolize and quote Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy of civil disobedience tend to be the first to criticize Colin Kaepernick’s even less disruptive non-violent resistance, let alone the blocking of a highway.

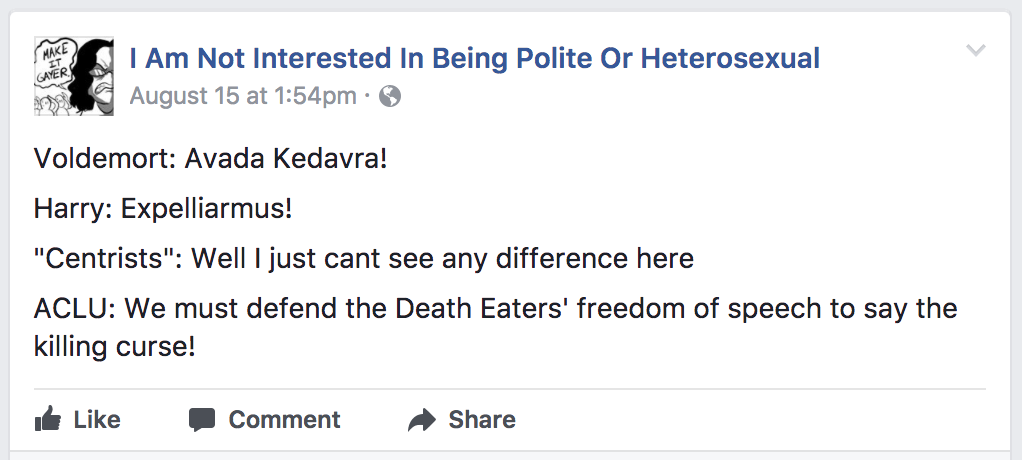

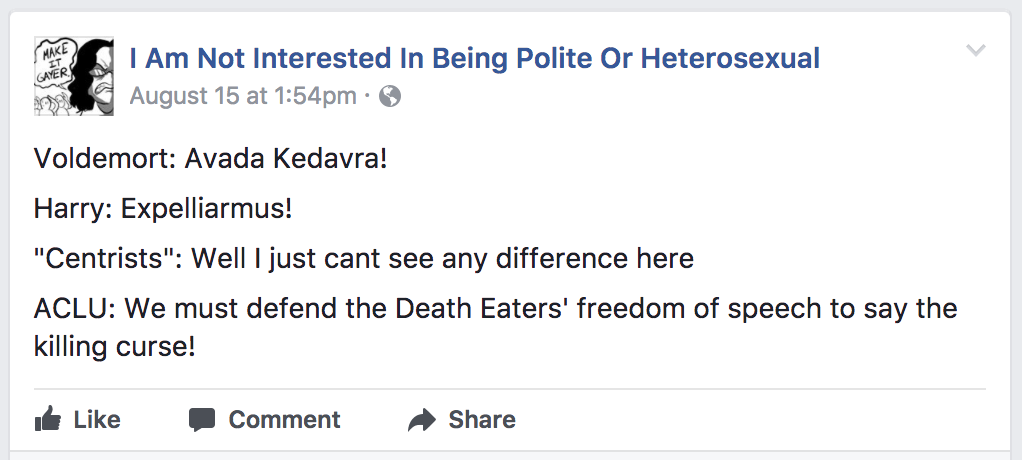

I’m not the first to make this observation, as evidenced by the many posts framing our current troubles in terms of Star Wars, or Harry Potter. Nor am I naïve in terms of why we root for idealized, allegorical representations of real life struggles and not their flesh-and-blood equivalents, or why dystopias are largely the real-life sufferings of brown and black people transposed onto white protagonists. But what drives me to hope and despair alike is the capacity, and failure, for fiction to breed empathy and imagination. Stories should not make us act like we’re living in a comic book, but they should inspire us to do more than cast a ballot every four or five years and spend the rest of our time crying into cake (no, I’m not going to let that go). They should expand the range of the politically possible. They absolutely have for the far-right, which has risen to prominence largely on iconography adopted from pop culture—ironically, often drawn from the very people they seek to eliminate, such as when the Alt Reich took the Red Pill from a film made by two trans women about a multicultural group of freedom fighters.

I’m not the first to make this observation, as evidenced by the many posts framing our current troubles in terms of Star Wars, or Harry Potter. Nor am I naïve in terms of why we root for idealized, allegorical representations of real life struggles and not their flesh-and-blood equivalents, or why dystopias are largely the real-life sufferings of brown and black people transposed onto white protagonists. But what drives me to hope and despair alike is the capacity, and failure, for fiction to breed empathy and imagination. Stories should not make us act like we’re living in a comic book, but they should inspire us to do more than cast a ballot every four or five years and spend the rest of our time crying into cake (no, I’m not going to let that go). They should expand the range of the politically possible. They absolutely have for the far-right, which has risen to prominence largely on iconography adopted from pop culture—ironically, often drawn from the very people they seek to eliminate, such as when the Alt Reich took the Red Pill from a film made by two trans women about a multicultural group of freedom fighters.

The most trite and popular fiction is chock full of examples of disobedience, civil and otherwise, unruly heroes who work outside of the system because the system is broken—often in far less dire straits than we currently find ourselves, with climate apocalypse looming and a legitimately cartoonish villain with his finger on the big red button. If you can understand why Panem doesn’t just elect a new president with better childcare policies, you should be able to understand why legitimate and unobtrusive channels don’t seem all that appealing to people who hunger for change.

“People would love it, and defend it with their lives because they would somehow know that their lives could be nothing without it.

If the Earth were only a few feet in diameter.”

This gap, between real things and representations of things, is at the heart of something I’ve been struggling to get my head around in recent months. The passion I see for stories, be they movies, games, or—gasp—sometimes novels, is something that I share, and yet it boggles me that as much as they affect culture in a broad sense, they seem to often have little impact on the individuals most devoted to them.

I

f the Standing Rock land defenders were nine feet tall, blue, and had pointed ears and cat eyes, would the viewers who made a shitty film $2.788 billion give some of that time and money in the fight against DAPL? If the cops gunning down unarmed black people in the streets were wearing Stormtrooper armour instead of blue uniforms, would white geeks sympathize with Black Lives Matter’s rage? If North Americans of different classes were divided into twelve large geographical districts rather than a patchwork of segregated neighbourhoods ripe for gerrymandering, would struggle against the 1% become a more palatable idea outside of the typical activist demographic?

f the Standing Rock land defenders were nine feet tall, blue, and had pointed ears and cat eyes, would the viewers who made a shitty film $2.788 billion give some of that time and money in the fight against DAPL? If the cops gunning down unarmed black people in the streets were wearing Stormtrooper armour instead of blue uniforms, would white geeks sympathize with Black Lives Matter’s rage? If North Americans of different classes were divided into twelve large geographical districts rather than a patchwork of segregated neighbourhoods ripe for gerrymandering, would struggle against the 1% become a more palatable idea outside of the typical activist demographic? Speaking as a responsible adult, we often worry about the messages young people take from media. Can a kid playing a violent video game distinguish between fantasy and reality (my own response to this is nuanced; in most cases yes, in some cases, actually not so much, or the military wouldn’t use video games for recruitment)? But I think in focusing on that, we often neglect to examine why these stories exist in the first place, and what we stand to learn from them.

This is the obvious reason for distinguishing fiction from reality, but I think most adults are able to do that. What is more confusing for me is that the social usefulness of such morality tales often gets lost in the shuffle.

I hate to be harping on the antifa thing with so many posts, but it’s a good example of where I feel lessons of fiction have utterly failed the casual citizen. The typical anti-antifa (dear fuck, what an awkward construction) post I see on Facebook focuses on two things: violence and masks. Because antifa are sometimes violent—even though in reality only a small number of antifa commit actual violence in a small percentage of anti-fascist work—and we dislike Nazis because Nazis are violent, the two are morally comparable. This is an easily debunked argument, though I imagine its proponents must have a difficult time wrapping their heads around, say, World War II.

I hate to be harping on the antifa thing with so many posts, but it’s a good example of where I feel lessons of fiction have utterly failed the casual citizen. The typical anti-antifa (dear fuck, what an awkward construction) post I see on Facebook focuses on two things: violence and masks. Because antifa are sometimes violent—even though in reality only a small number of antifa commit actual violence in a small percentage of anti-fascist work—and we dislike Nazis because Nazis are violent, the two are morally comparable. This is an easily debunked argument, though I imagine its proponents must have a difficult time wrapping their heads around, say, World War II. The mask issue is what I find more interesting. One meme I saw equated antifa to KKK, because both wear masks, and if you believe in your convictions, you wouldn’t hide your face. This was from a nerd, though journalists also ask this question frequently. Presumably, nerds and journalists are both familiar with the tropes of superhero comics, in which both heroes and villains often wear masks to disguise their identities.

“But wait, Sabs. You’re not living in a comic book! This is real life.”

Okay. But. Fiction exists for a reason, which is to tell us stories about who we are and why people do the things they do. Otherwise, there is no point to it; the stories we tell would have no resonance if they were meaningless.

So why does Batman wear a mask? Partially to invoke fear, but also to, oh, protect his friends from retaliation. To, to frame it in real-life terms, avoid getting doxxed. We can—and I do—argue that perhaps donating his copious billions to build up Gotham’s infrastructure and mental health services might go a lot farther in terms fixing the root problems plaguing the city, but I don’t think even the most hyper-critical pedant would argue that Batman’s failures are because he wears a mask. Or because he is secretly ashamed of his beliefs. Or even that he is morally equivalent to the villains he fights, either because of aesthetics (mask) or actions (violence), despite the existence of grimdark comics revisionism.

So why does Batman wear a mask? Partially to invoke fear, but also to, oh, protect his friends from retaliation. To, to frame it in real-life terms, avoid getting doxxed. We can—and I do—argue that perhaps donating his copious billions to build up Gotham’s infrastructure and mental health services might go a lot farther in terms fixing the root problems plaguing the city, but I don’t think even the most hyper-critical pedant would argue that Batman’s failures are because he wears a mask. Or because he is secretly ashamed of his beliefs. Or even that he is morally equivalent to the villains he fights, either because of aesthetics (mask) or actions (violence), despite the existence of grimdark comics revisionism.Of course, I am not just talking about violence—in fact, critiques of left-wing activism often, at their root, have little to do with what any reasonable person would deem violence. Any political action outside of state-sanctioned action—which is to say, voting, and possibly calling your representative if we’re feeling generous—meets with the most vicious criticism from people looking for an excuse to either disparage the cause or not do anything themselves. There is nothing remotely violent about, say, blocking a major street with a peaceful demonstration, but large swathes of the right and centre are quite comfortable with running over protestors who do so. They would prefer it, I suspect, if we did not push back at all.

This, despite the presence of myths that tell us to venerate individuals and groups that worked outside of the system, whether fictional or real. The Civil Rights movement may very well be a fairy tale for all that an average commentator knows about it; those who idolize and quote Martin Luther King Jr.’s legacy of civil disobedience tend to be the first to criticize Colin Kaepernick’s even less disruptive non-violent resistance, let alone the blocking of a highway.

I’m not the first to make this observation, as evidenced by the many posts framing our current troubles in terms of Star Wars, or Harry Potter. Nor am I naïve in terms of why we root for idealized, allegorical representations of real life struggles and not their flesh-and-blood equivalents, or why dystopias are largely the real-life sufferings of brown and black people transposed onto white protagonists. But what drives me to hope and despair alike is the capacity, and failure, for fiction to breed empathy and imagination. Stories should not make us act like we’re living in a comic book, but they should inspire us to do more than cast a ballot every four or five years and spend the rest of our time crying into cake (no, I’m not going to let that go). They should expand the range of the politically possible. They absolutely have for the far-right, which has risen to prominence largely on iconography adopted from pop culture—ironically, often drawn from the very people they seek to eliminate, such as when the Alt Reich took the Red Pill from a film made by two trans women about a multicultural group of freedom fighters.

I’m not the first to make this observation, as evidenced by the many posts framing our current troubles in terms of Star Wars, or Harry Potter. Nor am I naïve in terms of why we root for idealized, allegorical representations of real life struggles and not their flesh-and-blood equivalents, or why dystopias are largely the real-life sufferings of brown and black people transposed onto white protagonists. But what drives me to hope and despair alike is the capacity, and failure, for fiction to breed empathy and imagination. Stories should not make us act like we’re living in a comic book, but they should inspire us to do more than cast a ballot every four or five years and spend the rest of our time crying into cake (no, I’m not going to let that go). They should expand the range of the politically possible. They absolutely have for the far-right, which has risen to prominence largely on iconography adopted from pop culture—ironically, often drawn from the very people they seek to eliminate, such as when the Alt Reich took the Red Pill from a film made by two trans women about a multicultural group of freedom fighters.The most trite and popular fiction is chock full of examples of disobedience, civil and otherwise, unruly heroes who work outside of the system because the system is broken—often in far less dire straits than we currently find ourselves, with climate apocalypse looming and a legitimately cartoonish villain with his finger on the big red button. If you can understand why Panem doesn’t just elect a new president with better childcare policies, you should be able to understand why legitimate and unobtrusive channels don’t seem all that appealing to people who hunger for change.

no subject

Date: 2017-08-22 05:38 pm (UTC)I think there is a very powerful Liberal ideology - though actually it spans the range from moderate Conservatives to Social Democrats - whose key tenets are Democracy, the Rule of Law, and the State Monopoly of Legitimate Violence. Let's call it Liberal Democracy, or LibDem, for short.

This is not a Utopia, but (combined with Capitalism, regulated and softened to a greater or lesser extent) it is the best sort of society and governance humans can realistically achieve. Someone like Trump threatens to diverge from this, and is viewed with horror by pretty much the whole of this spectrum.

Within Liberal Democracy, there may well be problems and injustices, even quite serious ones, but they are potentially fixable from within the system. Going outside the means approved by the system to fix problems threatens to undermine the core principles of the system, which guarantees security, stability and broad social peace.

The forces of law and order, likewise, may have problems, even quite serious ones in some cases, but they can basically be trusted, within suitable governance structures, to be an impartial upholder of the Rule of Law and the security of the population. Again, the dangers of going outside the system to deal with problems (be that vigilantism or civil disorder) is more dangerous to the stability of LibDem than any problems they may seek to address.

LibDem is not really inspiring, it is really quite boring. It's just the best we can do. There is no room for heroes.

So the stories have their place in people's imagination, but they are seen as coming from times and places and worlds that do not conform to Liberal Democracy. Where there are tyrants and monsters and uncontrolled crime and violence, and heroes are still needed. They also resonate very much with national historical myths; the American Revolution, or World War 2, for example.

Violence is justified only where there are not peaceful ways of achieving change within the system. Civil disobedience or other illegal acts, only when there are not legal and democratic means - where LibDem does not apply. MLK and the civil disobedience of the civil rights movement can be justified and praised in retrospect (though of course at the time Liberals often decried it), because black people did not have recourse to legal and democratic means; the South can be seen, with the safe perspective of history and distance, as other than Liberal Democracy.

The idea that the comforting truths of LibDem are not actually a reality, or are not for a whole lot of people, is an incredibly disturbing and scary one for this worldview. That the police, for people of colour, are an oppressive occupying force and not an impartial protector and arbiter; that the police are not politically neutral but in fact actively hostile to progressive causes and protective of the far right; that the West's actions in the world are not only sometimes mistaken or excessive, but frequently brutal and tyrannical; these ideas meet with enormous psychological resistance - they are essentially intolerable. They undermine the fundamental sense of safety that privilege affords.

So the stories fail to create resonances with the contemporary situation, because the LibDem myth dominates how liberals view the contemporary situation. Instead, the stories occupy a mental space outside the safe but dull reality of Liberal Democracy.

Trump undermines this myth to some extent, but even so, the other, scarier myths and stories, are slow to penetrate into the idea of the 'real world' - at most they may do so in a trivialized form, e.g. adopting Star Wars symbolism as symbols of 'The Resistance', where The Resistance involves the Women's March and voting for Democrats.

That's my attempt to rationalize it, anyway.

no subject

Date: 2017-08-22 06:35 pm (UTC)There is also, it must be said, a racial component—probably the single deciding factor in the US (in Canada it's more indigenous vs. settler). In nearly every example I listed, save the real life mythologized figure of MLK, the unruly protagonist is white. The intolerable limits of the LibDem consensus as you put it, are not violence vs. non-violence, but white and Other. Or, Muggles can be killed en masse without more than a resigned concern, but the second a wizard falls, the situation is grave.

This is an awesome and thought-provoking essay. Have you considered submitting a version of it to something like Medium?

I have an utterly irrational fear that when I share my blather beyond an immediate circle of people who are interested in reading it, I will have these sad abandoned blog posts with zero comments. I say "irrational" but that's often been the case for more public-facing things I've written.

no subject

Date: 2017-08-22 06:21 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2017-08-22 06:36 pm (UTC)no subject

Date: 2017-08-22 09:11 pm (UTC)To be honest, I think some people are just too shitty and dense to think for a single second that might be acting like the villains in their favourite film.

FFS, New Testament stories tend to focus on stuff like compassion, kindness, self-sacrifice, humility, forgiveness, etc. and yet so many people who claim to be Christians and shout about the Bible don't seem to care about this.

Sorry if this sounds cynical or less thought out than your essay (which is really really good)

no subject

Date: 2017-08-22 09:22 pm (UTC)I often fear that in our haste to quantify literacy in the school system, we've failed at getting across the joy of reading, metaphor, and allegory. In fairness to the supposed Christians, the Bible is not an easy book to read compared to one's ability to memorize, or listen to other people's interpretations. There's a reason study groups and theological schools exist (not that they are any better than individual churches or families at analyzing what is actually meant by the Bible, but at least there's some pretence of more than simple rote learning.

no subject

Date: 2017-08-22 10:22 pm (UTC)This is true, but ime a lot of the stories tend to be explained in simple terms. This is why within so many Christian denominations, there are things like versions of the Bible for kids and animated movies with Bible stories. These things are presumably not made by people who don't know the Bible to begin with. I think that to grasp some of the very basics of the NT's message, you don't need to be especially good at reading it; that's part of why there are so many parables and the like, to make it easier to "get".

I often fear that in our haste to quantify literacy in the school system, we've failed at getting across the joy of reading, metaphor, and allegory.

I don't think that's the sole cause. I think some people maybe just don't like reading. It's hard for me to understand that, but I can see why it would be possible, in the same way that there are lots of hobbies and activities I'm just not into. The bigger problem is more about school systems not focusing so much on giving people skills to analyse and understand media across the board and applying those metaphors to their own lives, combined with many people just being downright shitty and not caring when it comes to pushing their bigotry.

no subject

Date: 2017-08-23 01:31 pm (UTC)capitalist consumer desires may be your issue here

Date: 2017-08-31 04:14 am (UTC)No, because the movie viewers were looking for entertainment. "Economic Development vs Native Protectors of the Environment" is a 'wicked problem' (no easy & complete solutions). People plunge into stories and fictional universes to take their mind off the real-world problems that they feel powerless to solve. Fictional movies make more money than documentaries.

Once a real world problem becomes simple Good vs Evil, it can be fictionalized, as in your Hitler-punching comic above. But if half the the comics market thinks Hitler is the Good Guy, and the other half thinks he's Evil, it's harder to sell comics. (American political discourse is currently bifurcated in this manner.)

Re: capitalist consumer desires may be your issue here

Date: 2017-08-31 07:50 pm (UTC)I do think that pop culture can have an impact. Witness the trend of women dressed up as Handmaids showing up to government buildings. Though of course, Handmaid's Tale is a far cry from Hunger Games.